Captain F.A. Wilson and Alfred B. Richards

The impelling motives for such a venture were the attempt to solve the problem of overpopulation in Great Britain with the concomitant matter of unemployment (pauperism), the colonization of British North America as a bulwark against the expansionism of the United States, and the opening up of an expedient commercial route to the Far East, part of a strategically secure “all red route.” By fostering a great emigration to build the railway, Britain’s greatness would be enhanced and British North America’s future assured. The line of railway was to run “as straight as the nature of the country could render it practicable” from Halifax to the Gulf of New Georgia and would cross territory 2800 miles in breadth, opening up land for settlement and agriculture and the exploitation of the vast resources to be found there. The line was to be divided into 7 sections each 400 miles in length.

No. 1, or the Atlantic Division, running from Halifax to Quebec. 400 miles.

No. 2, the Quebec Division, from Quebec to Tamiscaming Lake. 400 miles.

No. 3, the Lake Division, from Tamiscaming to Lake St. Anne. 400 miles.

No. 4, the Central Division, from Lake St. Anne to Fort Garry. 400 miles.

No. 5, the Prairie Division, from Fort Garry to Saskatchewan River (elbow). 400 miles.

No. 6, the Mountain Division, from Saskatchewan across the Rocky Mountains by Devil’s Nose to Upper Arrow Lake. 400 Miles.

No. 7, the Pacific Division, from Arrow Lake to New Georgia Gulf. 400 miles.

Total length: 2800 miles.

Each of the sections was described in terms of the potentialities of the country it traversed. Realizing that difficulties might be encountered in breaching the Rockies, Wilson and Richards tended to dismiss the problem by noting “...were not the chain broken by ravines which should offer a varied choice of passage; while we know that science, improved by the daily practice of railroad ascensions, can fortunately overcome far, far greater obstacles than these.”

Proposing the Use of Convict Labour on the Railways

All the physical resources necessary for building the railway were in place ready to be exploited, what was sorely lacking was labour.

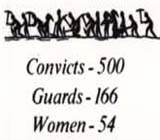

This situation was easily rectified by recruiting from the mass of “pensioners, paupers and prisoners” in Britain which were making enormous claims upon the public purse. Twenty thousand convicts were to be employed to “break ground and rough hew the line.” These were to be divided into seven divisions, each of 2800 men, the most obdurate being relegated to the western prairies and the mountains. When the railway was completed those convicts still serving their sentences would be established on Anticosti Island, which would be made into a permanent penal colony. To oversee the convicts, a body of 5000 men, to be know as the Pioneer Rifle Guards, was to be recruited, again divided into seven divisions. They were to be assisted by Canadian woodmen and Native peoples who would round up any convict deserters.

Augmenting the convict labour would be an army of 60,000 Civil Fencibles, drawn from the poor and unemployed and enrolled for three years. Though subject to military discipline, this would not be “allowed materially to affect their civil character, or interfere with the proper freedom of their general private habits, the innocent use of their leisure time, and their customary manner of performing their work.” These labourers would be divided into six sections of 10,000 persons each, with the provision that they would not be required to work in the mountainous areas. Each division would be subdivided into corps of 1,000 individuals each made up of 500 husbandmen and 500 artisans. An additional 600 women and children would be allowed to accompany each corps. Attached to each civilian corps would be two Chaplains, one surgeon and an assistant, two schoolmasters and two assistants. Available also would be a chapel, hospital, library, and reading room.

Each 400 mile division was to be controlled by the establishment of an headquarters as the centre. East and west of headquarters were to be located sub-stations, churches and forts. Work parties would work east and west from a central point in each segment. Wilson and Richards provided drawings and plans of barracks, block buildings, prisons, and women’s retreats. A uniform for the workers is also illustrated in their book.

The railway was to be built at an estimated cost of 5,000 pounds per mile, so that the total cost would be 14,000,000 pounds. This amount would be provided as a government loan and reimbursed as a result of the saving of the poor rate due to emigration, the increased value of the land served by the railway and revenues from the operation of the railway. Following Carmichael-Smyth, Wilson and Richards advocated an Imperial Commission to direct and manage the railway.

Convinced that British genius, capital and industry were equal to the task, Wilson and Richards concluded that “...grand works depend more on grand men than grand means.” A sentiment vindicated when the Canadian Pacific Railway finally spanned Canada.