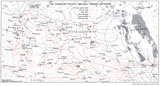

The Canadian Pacific Railway in Western Canada

Development of a Transcontinental Railway

Relatively little thought was given to the development of western Canada when the railway was first planned, although in a Senate debate on February 3, 1881 Sir Alexander Campbell considered, “ ... that construction of the railway was not the greatest part of their undertaking. They have undertaken ... to people a continent. If they do not send settlers in very large numbers into the Northwest it is impossible that the lands could be of any value, and the railway would be less than valueless ... .”2 In the event, the CPR was to prove instrumental in the development of the prairies, especially Alberta.

The contract3 for the construction of the CPR was signed on October 21, 1880. In return for $25 million and 25 million acres of land “fairly fit for settlement,” plus other incentives, the syndicate agreed to construct 1,900 miles of railway between Callander, Ontario and Kamloops, B.C. to connect with existing, or contracted lines. The route between these two points was not designated except that the line was to cross the Rockies through the Yellowhead Pass, immediately west of Jasper. Had the CPR followed this alignment, there is no doubt that Alberta would have developed in a very different manner to that known today.4

In late 1880, the Conservatives presented the railway act to the House of Commons, and it received royal assent on February 15, 1881. The following day, the syndicate deposited $1 million as security for the construction and the Canadian Pacific Railway Company came into being with a mandate to build a railway across the continent prior to May 1, 1891.

Rogers Pass

Almost immediately, the company engaged Major A.B. Rogers as locating engineer to find an alternative route to the Yellowhead Pass. In the past, a variety of reasons for seeking another route have been given. Some claim that Rogers’s route offered a shorter overall line while others state that the southern prairies presented fewer natural barriers. It has also been claimed that by locating the line to the south, U.S. lines were discouraged from coming northwards and siphoning off Canadian trade. However, writing an “Official Memorandum Respecting the Position and Prospects of the Canadian Pacific Railway,” dated November 21, 1881, George Stephen, President of the CPR, states quite categorically that “From the foot of the Mountains to Kamloops—a distance of about 450 miles, approximately—the line is being surveyed with good prospects of a shorter and better location being found than by way of the Yellowhead Pass.”5

The railway constructors, under the direction of General Manager, William C. Van Horne, struck westwards from Winnipeg on a southerly route while Rogers searched for a suitable pass through the Selkirk Mountains. Eventually, he succeeded and on July 24, 18826 a north-south running pass was discovered. When the news of the discovery of the Rogers Pass reached Montreal in August, construction was near Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.7

In the spring of 1883, the government agreed to the relocation of the line but indicated that no subsidies would be paid nor any land grants made for construction west of Moose Jaw until an independent evaluation of the Rogers Pass was made. From Moose Jaw, the route could be relocated through the Yellowhead Pass with a significant, but not insurmountable, diversion. The railway chose to forge ahead and Sandford Fleming, who had surveyed the original route through the Yellowhead Pass, was contracted to examine Rogers’s route. In August and September 1883 he went over the alignment and to Rogers’s great relief and surprise, Fleming reported, as told by Stephen, that he found the route to be “ ... quite practicable and highly satisfactory.”8 By the time Fleming’s report reached Montreal, the railhead was about to enter the Rockies at Gap.

Construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway

With a mandate to construct the line as rapidly and economically as possible, Van Horne’s rail laying contractors entered what is now Alberta, immediately east of Walsh in early May 1883. This was then part of the Assiniboia District of the Northwest Territories. Construction continued rapidly and Medicine Hat, 659 miles west of Winnipeg, was reached on May 31, 1883. After crossing the South Saskatchewan River, the contractors were in gently rolling, dry grassland and able to make excellent progress towards Calgary, 840 miles west of Winnipeg. Calgary was reached, with the completion of a bridge over the Bow River, on August 10th.9

From Calgary, at an altitude of 3,438 feet, the line followed the Bow River, rising gently at 13+ feet a mile over the 81.9 miles to Siding 29 (Banff). Progress was now more difficult and during September the railhead moved forward only a mile a day. By the end of October, the line was west of Castle Mountain, ascending at 15 feet a mile. From Laggan (Lake Louise), the line swung away from the Bow River and, at a steady 2.2 percent grade (116 feet per mile), approached the Continental Divide. Winter conditions halted construction in November, just over a mile short of the divide and heavy snows delayed the recommencement of work until May 1884. The final stretch of the mainline to the border were constructed quickly and the track layers entered British Columbia on May 25, 1884.10

Settlement and Transcontinental Service

The railway made possible rapid and economic access for passengers and freight and, to take advantage of this traffic, regular passenger service to Winnipeg commenced in December 1883. But the CPR had to find settlers for the land it had been granted. Settlers meant incoming supplies and outgoing crops and animals—all of which generated revenue. To promote settlement, the CPR opened offices in Europe, advertised the land in over 300 newspapers and even had a train encouraging life in western Canada tour throughout Britain. In 1884, the influx of settlers began and Calgary’s population grew to around 1,000. The line round the north side of the Great Lakes was completed in May 1885 and transcontinental service commenced in mid 1886. The CPR had fulfilled its first objective-connecting the country with a railway from coast to coast. For this, the CPR received a federal main line grant of $25,000,000 but would eventually receive 18,206,628.6 acres of land, 9,805,446.5 of which would be in Alberta.11

George Stephen in his Official Memorandum recognized the importance of the Pacific traffic and noted “With all the advantages it will possess of less mileage, easier grades, of using its own rails from ocean to ocean, and probably free from bonded debt, the Canadian Pacific Railway will be in a position to command its full share of the traffic from China and Japan, which is now carried by the Union and Central Pacific ... .”12 To promote trans-Pacific traffic, the company appointed agents for Japan and China and in 1886 seven sailing ships were chartered to carry freight to Canada. The first of these to reach Canada, the barque W.B. Flint, arrived on July 27, 1886, only three weeks after the first transcontinental train arrived on the west coast.13 Her cargo primarily comprised tea for Toronto, Hamilton and New York. Gradually coast to coast passenger traffic followed as steamships were introduced onto the Pacific service. By 1890, the company had a British Post Office subsidy to carry mail from Vancouver to Japan and China.14

The Canadian Pacific Railway in Alberta

The through traffic had little effect on Alberta’s development apart from providing some employment, primarily at the original division points at Medicine Hat, Gliechen, Canmore and Laggan (Lake Louise). Van Horne, however, saw the potential of the Rockies for tourism and the company’s first hotel in Alberta was opened at Banff in 1888. In 1890, the federal government authorized the Calgary & Edmonton Railway to construct branches from the mainline to Edmonton and southwards towards Fort Macleod. Although constructed by a nominally separate company, the CPR operated the two branches from their inauguration. These were the first standard gauge branch lines in Alberta and were built to develop local traffic by connecting the two major cities and open up the farm land immediately east of the Rockies.

The first branch line built in Alberta was the North Western Coal & Navigation Company’s 108-mile narrow gauge line from Dunmore to Lethbridge. This was an independent company and the line was constructed to carry coal from Lethbridge Coalbanks for sale to the CPR as fuel for its locomotives. In 1893, the CPR leased the line and converted it to standard gauge. It was purchased in 1897 as the first stage of the Crowsnest route. Building westward from Lethbridge, the new line was opened in October 1898 to Kootenay Landing, B.C.

Branch Lines

Contrary to popular opinion, the CPR did not embark on a branch line building program immediately after the mainline was opened. It did not have the finances to invest in such ventures and much of the land close to the mainline in southern Alberta was unsuitable for farming without irrigation. With the change of route from the Yellowhead Pass, the mainline penetrated a much drier part of the prairies than first planned. When the line was completed, the company established a number of experimental farms15 in Saskatchewan and Alberta along the mainline but found that the bulk of the land in this area was unfit for dryland farming. The railway did not have to accept land unsuitable for settlement and the CPR was not prepared to take the acreage available close to the mainline through southern Alberta. Instead, land was selected from areas far removed from the mainline. The North-West Irrigation Act of 1894 allowed the development of land in the drier areas and in 1903 the company selected its final land grant acreage.16

The arrival of the Edmonton Yukon and Pacific Railway in Edmonton in 1902 marked a turning point in the CPR’s thinking. It no longer enjoyed a monopoly in the west and, to protect its interests against the aggressive Mackenzie and Mann railway, it finally began to construct the branch lines necessary to develop its Alberta land holdings. The period between 1900 and 1914 was Canada’s golden years and the prairies experienced the first of a series of booms. This culminated with the discovery of oil at Turner Valley, just south of Calgary, but was snuffed out by the outbreak of World War One on August 4, 1914.

With free land in the western United States now settled, immigrants poured into western Canada and the railway experienced a number of very profitable years. This provided the resources for an extensive branch line program and the first lines in Alberta were the Wetaskiwin and Lacombe Subdivisions in the north central part of the province. Both were chartered by the Calgary and Edmonton Railway but were completed by the CPR. Between 1905 and 1916, the railway constructed some 900 miles of branch lines in Alberta.17

Competition from the Canadian National Railways

Following the war, the federal government became more involved in the development of Alberta. Both the Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern Railway were absorbed into Canadian National Railways and, with lines through the Yellowhead Pass, were well-suited to develop the northern portion of the fertile belt. New types of wheat enabled crops to grow at higher latitudes and the land around the two new lines was ready for development.

While D.B. Hanna was president of the Canadian National Railways, this did not cause much problem as he was content to operate the railway as economically as possible in order to manage its considerable debt but, in 1923, he was replaced by the aggressive and innovative Sir Henry Thornton.18 He had no qualms about the railway’s debt and from 1923 to 1931 both the CNR and the CPR constructed extensive branch line systems in the western provinces although there was relatively little head to head competition in Alberta. With its land grant acreage in the Edmonton area, the CPR was determined to protect “its” traffic and “invaded” areas which had previously fallen under the influence of Canadian National. In 1928, Edward Beatty, CPR’s president, stated, “I decline to acknowledge the right of the Canadian National to claim any part of Canada as a special preserve, and I intend to proceed with my own programme.”19 Nevertheless, such talk did not preclude cooperation with the CNR and on January 29, 1929 CPR and CNR took over ownership of the 900-mile Northern Alberta Railways from the Government of Alberta.

The 1929 stock market slump and the subsequent Depression brought an end to the intense competition between the two railways. From 1923 to 1931, the CPR constructed a total of 2,266 miles of track throughout the system and all but 145 miles of this was on the prairies.20 Construction of branch lines in Alberta amounted to over 600 miles of track. Had it not been for the Depression, when farm income fell to less than 20 percent of what it had been in the late 1920s, and the construction of good roads by the provincial government, northern Alberta would have had a system of railway branch lines in harmony with local requirements. During the Depression, both railways were criticized for what was considered to be severe overbuilding but in fact there was very little duplication of track. After the building programmes announced in 1928, the railways lived in relative peace as they could no longer afford the rash competition of the 1920s.

The Canadian Pacific Railway After World War II

When peace returned again in 1945, the CPR had to face another competitor. This time it was the road vehicle that competed with both railways. The car and truck made incursions on both the passenger and freight services of the railways. With this increased competition and freight rates held at unrealistically low levels, the extensive system of branch lines was too costly to maintain.21 Since 1960 the CPR has curtailed its branch line system considerably.

Notes | Bibliography | Abbreviations

1. G. Musk, Canadian Pacific: The Story of the Famous Shipping Line (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1981), p. 11.2. Senate Debates.

3. 44 Victoria, Chapter 1, 15 February 1881 ; H.A. Innis, A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), p. 95.

4. F.G. Roe, “An Unsolved Problem of Canadian History,” The Canadian Historical Association.

5. George Stephen, President, Canadian Pacific Railway, “Official Memorandum Respecting the Position and Prospects of the Canadian Pacific Railway,” Montreal, 21 November 1881, p. 2. Note: On hearing of Major Rogers discovery of the pass that bears his name, W. Kaye Lamb states: “Stephen was relieved and delighted. ‘I felt sure from what Major Rogers had told me last year, that we should succeed,’ he told Macdonald, ‘but was very glad to have my impression confirmed. This secures us a direct short through line, and adds greatly to the commercial value of the line as a transcontinental line’.” K. Lamb, History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1977), pp. 116–17.

6. P. Berton, The Last Spike, Vol. 2 of The National Dream: the Great Railway, 1871–1881 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1971), p. 162.

7. O. Lavallée, Van Horne’s Road (Toronto: Railfare Enterprises, 1974), p. 73.

8. W.K. Lamb, A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1977), p. 117.

9. Berton, The Last Spike, p. 244. Berton also states that a construction train arrived on August 12th, followed by one with a temporary station on the 15th. Lavallée states, “The question [site of station] was settled on August 15th. When the first construction train reached the site now occupied by Palliser Square, and gangs began to put down sidings and erect a station” (p. 95). Lamb states that “Steel reached Calgary on August 13 ... ” (p. 87).

10. Lavallée, Van Horne’s Road, p. 173.

11. A.S. Morton and C. Martin, History of Prairie Settlement, pp. 302–3.

12. Stephen, “Official Memorandum,” p. 4.

13. G. Musk, Canadian Pacific: The Story of the Famous Shipping Line (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1981), p. 12.

14. Ibid., p. 15.

15. Morton and Martin, History of Prairie Settlement, p. 251.

16. Lamb, p. 251.

17. Canadian Pacific Railway, Western Lines, Memorandum of Mileage, n.d.

18. Lamb, History of the Canadian Pacific Railway, p. 311.

19. Ibid., p. 313.

20. Ibid., p. 311.

21. Ibid., p. 425.